Blake Butler had given up on publishing Decade. He’d written the novel in 2008, and its complicated structure and dense language rendered it virtually unpublishable by both commercial and avant-garde standards. For years, he set Decade aside, occasionally opening the Word document and scrolling through as fast as he could, remembering all the work he’d done, then closing the window.

Then this February, as NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, flooded the Internet, everywhere from Twitter to The New York Times, Butler had an idea: he turned that scrolling action into a GIF, pages flashing before the viewer’s eye, and minted the GIF as a non-fungible token. With cryptocurrency, a buyer could purchase proof of ownership of Decade, represented by the GIF, as well as receive a PDF of the novel upon purchase. Overnight, a stranger bought the NFT for 5 ethereum—a $7,569.50 value at the time, now the equivalent of $12,377.30, much more than Butler had made off several of his published books. Said Butler, the sale was “like a bolt of lightning to his brain.”

The buyer, who goes by the pseudonym null_radix, bought Decade because he was “curious what was inside.” When he read it, Null_radix didn’t understand Decade, but he still has no plans to resell. Now, Decade sits in null_radix’s digital wallet next to a picture of a forest and a pair of digital socks.

It’s hard to make sense of what the NFT creative landscape might mean for otherwise underpaid writers. At once, it’s a place for writers to experiment with form, publish and earn money directly and instantaneously without any traditional publishing gatekeepers. It’s also a brand-new subculture with no reliable routes to financial success or readership, cut off from a larger writing market and culture that doesn’t understand it, raising knotty questions about what elements of writing are truly valuable to readers. For some, it’s exciting. But it’s also chaos.

*

Let’s start with the basics—in this case, the technicalities. An NFT, a non-fungible token, is a digital asset backed up by the ethereum blockchain that represents a real-world or digital object like a piece of art or a video. Essentially, when you buy an NFT, a network of computers records the transaction and gives you “proof of ownership” of the object the NFT represents. (Even if everybody else can see the object: if I buy the NFT of Nyan Cat for $600,000, everybody still has access to the GIF. I just get to say that I own it, because I do.)

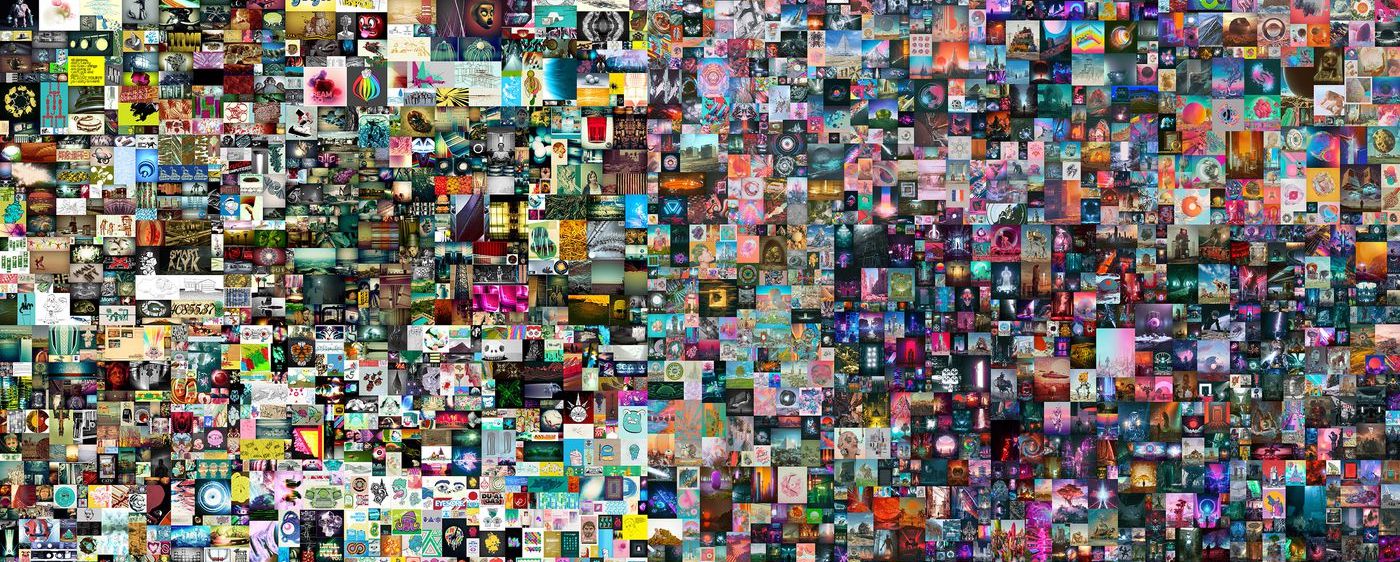

The past few months have seen a craze for visual art NFTs; collectors are using NFTs to buy and sell digital art for increasingly steep prices, and mainstream art institutions have gotten in on it. In March, digital artist Beeple sold a piece in a Christie’s auction for $69.3 million.

But an NFT doesn’t have to be a meme or a piece of visual art. It can be anything digital—a trading card, a newspaper article, or even a novel. Because the object represented by the NFT isn’t actually stored on the blockchain, writers can customize the way selling their writing NFTs represents their art. In its most basic form, NFT technology can be used like an ebook: a writer can mint an NFT of a book’s cover and then sell it, and offer the text of the book as a file that can be unlocked upon purchase of the NFT. Several self-published novels like this, attempting to cash in on the NFT trend, claim to be “the first NFT novel.”

But this isn’t the way most writers are working with NFTs. Instead of just tokenizing pieces of text, a new crop of “crypto writers” are using NFT technology in a multiplicity of eye-catching, innovative ways to finance their writing and interact with online consumers. On the more traditional side, Butler turns his novels into visually striking GIFs. Writer Rex Shannon is releasing each page of his novel CPT-415 as an NFT, and each page is made available to the public once it’s sold—so it essentially functions like a time-staggered Patreon, each buyer helping fund access to an ongoing body of work.

More inventively, NFT writing can also reforge the otherwise taken-for-granted relationship between reader and writer. The Italian artist Brickwall runs a collaborative writing project called The Chaintale, where buying the latest writing NFT in the series gives you the right to pen the next installment. Kalen Iwamoto, a crypto writer who runs a popular crypto writing Discord server, as part of a larger installation focused on femicide and violence against women, wrote a short piece that appears as a video of limbs and other body parts with sound, but if you purchase the NFT, download the file and change the extension to PDF, you can read her written piece on her own gendered experience. This is truly crypto-native writing, where form is married to theme and content. The transaction is a critical part of the art.

NFTs are a way for experimental writers to experiment with form—especially writers whose interests lie in technology. Butler was a computer science major in college and has been active in crypto for a while; his latest traditionally published novel, Alice Knott, deals with art’s perceived value and digital trends. For him, NFTs are a logical tool of expression. Rex Shannon’s work is heavily inspired by video games and levels, hence the serialized format: “The Internet is so much a part of [my novel] that it only made sense for the Internet to be of its platform,” he told me. “NFTs are of-the-Internet, and so is my book.”

Most of the writers in Iwamoto’s crypto writing Discord are grappling with themes of future technology; there’s a plurality of sci-fi writers, and not too many writers are working on traditional novels. Many writers are also writing in collaboration with artificial intelligence on their NFT pieces. Recently there’s been a lot of talk in print book circles about the “internet novel”: how do you accurately, meaningfully represent a technology as sprawling, as dense as the Internet via a print medium? Maybe you don’t; maybe you use digital tools themselves. NFT writing is one answer to the question of what “internet writing” in a digitally native age might look like.

Or maybe it’s just “writing.” Print books are an old technology, created when we had fewer tools at our disposal. Now, the Internet is one of the main ways to absorb information. Ebooks merge the familiar format of print with the new, the digital; as the Internet grows more familiar, it’s possible we’ll slowly see a move away from that transitional technology and toward new, digitally minded ways of organizing information and creating narrative.

It’s a place for writers to experiment with form, publish and earn money directly and instantaneously without any traditional publishing gatekeepers.Ability to play with form is an alluring feature of NFT writing—but NFT writing’s chief appeal might be its decentralization. With NFTs, writers can release their work and build direct relationships with their buyers and readers on their own time, with no gatekeepers or middlemen. No publisher is telling them what’s sellable. There’s also no expectation to create regular, consistent content for a consistent audience like on a Substack or Patreon. Said Butler on minting his writing as NFTs, “I was stunned to feel able to create exactly what I want, the way I want it, and distribute it when and how I want it.”

NFT writers can still mimic traditional forms of distribution and profit while retaining control over when to distribute their work. NFT-selling online platforms like OpenSea or Mirror let artists build into the terms of their NFT that they get a cut of secondary sales, similar to traditional book royalties. Creators can build their distribution system how they want. As Iwamoto puts it: In the crypto world, artists rule.

*

But what kind of kingdom do they rule over? Though artists have more control than they would in a traditional publishing market, how much power they have and how much money they can make is wildly unpredictable. Art collectors have purchased image-based NFTs for hefty prices, expecting their value to appreciate over time—just like art collecting works in the physical world. This week, pieces in Sotheby’s “Natively Digital” NFT art sale raked in hundreds of thousands—even millions—of dollars per NFT. Some media stories on NFT art have framed NFT buyers as soulless investors seeking profit for profit’s sake. Not so for crypto writing, notably absent in “Natively Digital.”

There is currently no substantial secondary market for crypto writing, at least according to the crypto writers I spoke to. Art collectors getting into the NFT space are collecting visual art, not writing. The majority of crypto writers aren’t well-known outside of crypto spaces, and the form is so new that value hasn’t appreciated yet.

It’s difficult for writers to predict which pieces will do well on the market, even based on previous sales. After selling her femicide piece for 18.888 ETH (now about 50,000 USD, about 30,000 at the time), Iwamoto priced her next multi-NFT project at .08 ETH each, but she only sold eight NFTs out of the fifty in that project, and had to split the profits between her and her twelve other collaborators. In order to find buyers for their pieces, writers have to be their own marketing and publicity department. Said Iwamoto, “In general, selling your NFT depends a lot on whether you’re communicating and connecting with the community, which for now happens mostly on Twitter.”

Many crypto writing buyers are other crypto writers and artists supporting each other’s work. Iwamoto tries to spend part of what she earns from her crypto writing on buying other crypto writers’ art to support the fledgling crypto writing community. Butler also buys crypto art and writing.

NFT writers can still mimic traditional forms of distribution and profit while retaining control over when to distribute their work. In the crypto world, artists rule.When crypto writing does make it outside a circle of fellow crypto writers, it’s usually to people already heavily involved with cryptocurrency. Rather than investing with the express intent of reselling, most buyers just have a particular interest in digital art or NFTs as a conceptual project. Ddaavvee, the buyer of another of Butler’s NFT “novels,” studied book binding in college and was interested in Butler’s use of a GIF as a sequential book-binding tool. He hasn’t even read the book he bought, as he plans to unbind the GIF and make it readable for himself (an “added challenge”). He doesn’t currently have any intention of selling. Said Ddaavvee, “My intentions have always been to amass a collection worthy of a museum, but selling the right pieces to other collectors affords the liquidity for acquiring more pieces.”

Null_radix has never resold an NFT. He doesn’t even think of his NFT acquisitions as investments: “NFTs don’t seem to me to have value that can be defined as easily as ‘owning a piece of art.’ It’s more some sort of collective geist. The draw is the insanity of it all.”

*

Null_radix makes a good point. When a buyer buys an NFT, they’re buying a relationship with the art; they’re buying access to whatever experience of the art is only accessible to buyers; but they’re also buying the ability to be a person who has bought an NFT, to indicate they are both tech-savvy and creatively minded, to even get to be a part of the conversation about the significance of NFTs. The arbitrariness of NFT’s value is itself a talking point.

According to Ddaavvee, NFTs have become a kind of replacement for social networks in the crypto community: “They’re a way to identify who has similar interests to you and see how much they put on the line to secure their spot in whatever community they’re a part of.” Ddaavvee is uniquely poised to observe this; his crypto windfall came in 2017, when he bought one hundred Cryptopunks, unique collectible 24-by-24 pixel characters often used as social media avatars. As their price shot up, he sold a few for enough ETH to fund all his future crypto art and writing purchases. A “Covid Alien”-themed Cryptopunk just sold at Sotheby’s “Natively Digital” sale for nearly $12 million. We can understand a Cryptopunk—and to some extent, any NFT, including writing ones—as a digital Pokemon card or Funko Pop. Owning and displaying them is a project of establishing “coolness” in a specific subculture, establishing selfhood through curation.

*

The crypto “communities” Ddaavvee references are largely separate from the bigger print writing community. There has not been a major move from literary fiction writers to using NFTs; the writers using NFTs are largely already crypto-savvy. It’s not that NFTs function freakishly differently from print; a writing NFT is similar to a first edition or rare book in that X. One can imagine rare book collectors collecting NFTs. But there has been no visible overlap in these markets, likely because of confusing signifiers. All the obvious tells of “value” on a rare book—yellowing pages, era-specific binding, the author’s handwriting—aren’t present on an NFT. And, reductively, rare books are old; NFT writing, for the moment, is flamboyantly new.

If you think about NFTs too long, you’ll end up staring into the maw of value theory; if you’re not already familiar with cryptocurrency, it’s hard to wrap your head around, to say nothing of the technological barrier to entry. Just look at the series of articles in mainstream publications over the past few months trying to explain NFTs in layman’s terms. And with no robust secondary market for crypto writing, there’s not an incentive for those not already in the know to put in the effort.

“NFTs don’t seem to me to have value that can be defined as easily as ‘owning a piece of art.’ It’s more some sort of collective geist. The draw is the insanity of it all.”Beyond the vague notion that NFTs are “in” right now and will gain value, there’s not a clear incentive for mainstream publishers to expand into the NFT space. Readers of print books are not pushing for NFT books, and print book sales aren’t flagging; in fact, they’ve been steadily rising since 2012, even during the COVID pandemic print sales rose 8.2 percent in 2020, and ebook sales still make up only about 20 percent of all book sales. NFTs haven’t even entered discussions in most digital book spheres: Heather McCormack, Vice President of digital library CloudLibrary, said, “I don’t see the value in [writing NFTs], frankly. They have not entered internal conversations at this point because library patrons have not asked us for them because they are all too happy with what we already give them: books.”

Plus, the styles and focuses of many crypto writing works place them in a category of genre fiction that doesn’t overlap with literary publishers. Anne Trubek, founder and publisher of Belt Publishing, was intrigued by NFT writing as a way to play with the ideas of reproduction and rare books, but when she looked for work to purchase she was turned off: “I found that everything was inordinately expensive, the creators insanely male-dominated, and the works themselves of little interest.” Though there are female creators making interesting NFT work, the most high-profile artists—most visible to a casual explorer—are men.

*

Some might view publishers’ lack of enthusiasm as typical of an industry that doesn’t want to change. But it also hits upon a potential difference between what “proof of ownership”—and its value—means in the traditional publishing world as opposed to the crypto world. For NFT buyers in a crypto-driven social scene, “proof of ownership” means keeping an NFT in your digital wallet for possible friends to see. It’s similar for visual art buyers; “proof of ownership” of physical visual art is being able to display it, hang it on your wall. But for readers, aside from rare book collectors, it means less to physically possess a lot of (mass-produced) books than to have spent time with a lot of writing, to know one’s way around it.

“Proof of ownership” in most writing-driven social scenes isn’t so much about owning collectibles as it is about being able to hold your own in an intellectual conversation or dash off a Twitter bon mot about the new Sally Rooney. (Or whatever you’re into.) Thus, a writing NFT doesn’t translate as neatly, profit-wise, as a digital art NFT. “At the risk of sounding like a traditionalist, which I am not,” said McCormack, “proof of ownership in my view is having read the damn book and being able to talk about it with your friends or colleagues in book land.”

*

The annoyance goes both ways: if traditional publishers enter the space, they may not be met with open arms, as decentralization is the central ethos of NFT writing. Other than traditional legitimacy, it’s unclear what value publishers can add to crypto writers’ experience. Even traditional distributors feel somewhat obsolete here. The German digital distributor Bookwire is launching a new NFT marketplace this fall; what can they do that existing crypto marketplaces like OpenSea or Mirror can’t?

A few crypto-knowledgeable groups are already entering the NFT writing space as publishers—yet it remains to be seen if they’ll stay the course. WIP Publishing, which markets itself as the “very first crypto publishing house,” for the time being only lets writers create very basic unlockable PDF books, locking out other more crypto-native types of NFT projects, and appears to act essentially as a self-publishing platform. (Their website says they “educate authors to act as their own promoters, agents, and so on.”) Posited Iwamoto, “My feeling is that the publishers that will succeed are those that know the space really well and bring something more or new or innovative. I don’t know if the traditional publishing model will work in this space.”

“At the risk of sounding like a traditionalist, which I am not, proof of ownership [of a book] in my view is having read the damn book.”This may not even matter in a few months. Protos recently released new data that says the NFT bubble may have popped: there’s been a 60 percent decrease in daily sales since May, and the entire first week of June only saw $19.4 million in NFT sales, down from a peak of $102 million in one day. Reports aren’t definitive—this may just be the downswing of a cycle that will repeat—but ETH is down, and it’s possible the initial NFT craze is over.

Also stifling interest and raising concern about NFTs’ sustainability is NFTs’ chilling environmental cost. The ethereum blockchain, on which the majority of NFTs are built, is purposefully energy-inefficient. For security and value-sustaining reasons, it forces ethereum-mining computers to solve complex equations in order to add their assets to the blockchain, which grow more complex and energy-draining as ETH becomes more popular. (Think warehouses full of giant computers burning through electricity.) Ethereum uses as much electricity as all of Libya, and the digital artist Memo Atken calculated that, due to the blockchain transactions involved in minting an NFT, the average NFT has a carbon footprint equal to over a month of the average EU citizen’s electricity usage. Ethereum has claimed for years they’ll move to a more energy-efficient model, but the process has been laughably slow: it’s a joke among crypto users.

A few crypto writers are tapping out due to environmental worries; Rex Shannon, the serialized novelist, has stopped working in the medium. Others are switching to NFT-selling platforms based on more energy-efficient blockchains, like Tezos, but alternate cryptocurrencies lack the popularity, and thus stability, of ethereum. Environmental concerns limit NFTs’ appeal to the traditional book world: said McCormack, “My overriding impression is that most book people think NFTs are a stupid environmental menace.” It’s unclear whether publicity around ethereum’s environmental impact will eventually kill NFTs for good—or whether their popularity will continue as we march deeper into climate crisis.

But the crypto writing stalwarts aren’t worried about unknowns. For them, the excitement lies in building community and playing in, exploring, an unformed space. The uncertainty about the future of NFTs—the sense that it’s all a big experiment—is, in a way, the great appeal of it all. “It feels like a moment for reinvention, where the field is as wide open as you could want,” said Butler. “Let’s get weird.”