When I was a girl, I had a friend.

Some years I used honorifics and some years she was my only friend and there was no need. There was a high school classmate of ours who, for a while, thought we were the same person, and there was another who thought we were lovers. Ive told the story of the end of that friendship so many times that it has almost lost meaning. At first, telling the story stretched out all the space between us that hadnt been there before. Then, it just began to collapse it.

One time, our senior year, I told the story to another girl in the winter darkness of my suburban street. Her car was sporty. The parking brake was a pedal by her feet. When I told the story she lifted one long leg and smashed that parking break to the floor.

The parking brake and the totality of being a teenager made me think it was a good storya high school band put it in a song. From time to time, in the fifteen or so years since, Ive taken that story out again and held it up to the light. Frances Ha appeared on the scene, Elena Ferrantes Neapolitan Quartet, Lady Bird, Conversations with Friends, all stories about female friendship and its fucking sharp points. I recognized elements of myself in each of them, and it quieted all that teenage rage. I was not the only girl to have her heart broken by her best friend. But I hadnt yet read Sula.

Toni Morrison is a writer who doesnt write to teach a lesson, as she has said, but Sula taught me one anyway. Sula seems to be about dependence: womanhoods dependence on motherhood, a mothers dependence on her children, a woman on her lovers attention. But it also about the way a friendshipa very close oneis a relationship built out of desire, independent from all rules.

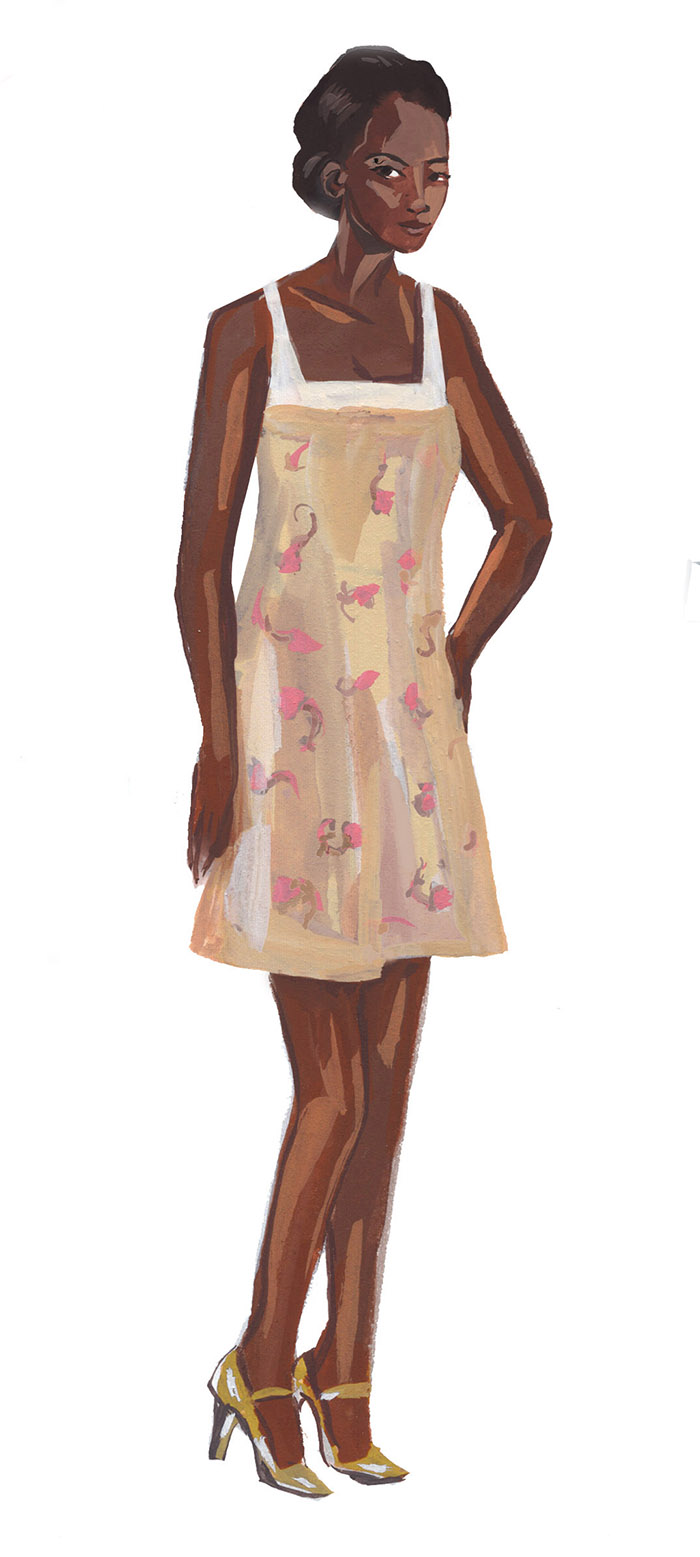

The novel blooms and blooms: the grandmothers behind the two mothers behind their daughters. Its the story of life in one black neighborhood, the Bottom, in rural Ohio from 1895 to 1965. In 1922, Sula and Nel find each other: Their meeting was fortunate, for it let them use each other to grow on. One day, a game they are playing leaves a boy drowned in the river. The secret, held in the sanctity of friendship, becomes part of their inseparable bond. When the girls grow up, Nel marries and Sula leaves town for college and whatever else she can find. Had she paints or clay, or knew the discipline of the dance, or strings; had she anything to engage her tremendously curiosity and her gift for metaphor, she might have exchanged the restlessness and reoccupation with whim for an activity that provided her with all she yearned for. Like any artist without no art form, she became dangerous. Nel, meanwhile, settles into the expectation of the town. Unfulfilled and fabulous, Sula returns. She arrives arranged in a sophisticated traveling costume the likes of which the town has never seen. She retires, eventually, to a plain yellow dress but the point is made. Sula has journeyed beyond the Bottom and this new version of her has no use for the towns careful social codes. The rumors swirl, about how she is never ill, about how she comes to church without underwear.

She returns for Nel, but the arithmetic of best-friendship comes out wrong. She had clung to Nel as both the self and the other only to discover that she and Nel were not one and the same thing. Sula learns her terrible lesson two ways: first, she sleeps with Nels husband, thinking their friendship is stronger than her curiosity. It isnt. Then, alone for perhaps the first time, she develops an attachment to a man who wants none. This final break doesnt kill her, but something does. She is deadless than four pages later.

Perhaps she was dead to Nel and could therefore live no longer. Perhaps there is a tiny sliver of bitter revenge in Sulas death. Or perhaps she has to die for Nel to realize the truth about friendship. To learn the lesson that the impossible female friend will always be held in the impossible balance. Only on her deathbed can Sula speak with full honesty: If we were such good friends, how come you couldnt get over it? It takes Nel twenty-five years, but she finally hears Sulahears her loud and clear and wonders, really wonders, what the answer is.

If friendship is all we say it is, if friendship in girlhood is the mingling of two souls, companionship that no adult, no lover, can ever match, then how can any transgression be unforgivable? Why isnt the friendship sovereign over all possible faults? All these years later, Im still wondering, How come I couldnt get over it?

*

The purple dress:

On a particularly fateful day in her twelfth year, Sula wears a purple and white dress with a belt. Later in the book, the grammar of memory gets confused, the words mingle and redistribute, and it is as if Nel were the one wearing the dress, Standing on the riverbank in a purple-and-white dress, Sula swinging Chicken Little around.

The return:

Sulas return to the Bottom after her time away is one of literatures most stylish entrances. She was dressed in a manner that was as close to a movie star as anyone would ever see. A black crepe dress splashed with pink and yellow zinnias, foxtails, a black felt that with the veil of net lowered over one eye.

The red leather case:

Morrison carefully catalogues each item Sula has with her when she arrives back in town, including a red leather traveling case, so small, so charmingno one has seen anything like it ever before, including the mayors wife and the music teacher, both of whom had been to Rome.

The yellow dress:

Within just a few days of returning, Sula has settled into wearing a plain yellow dress the same way her mother, Hannah, had worn those too-big house dresseswith a distance, an absence of a relationship to clothes which emphasized everything the fabric covered. There is an easy dichotomy to draw between women who want attire to complement their figures and women who want their figures to defy their clothing. When rumors begin to circulate that Sula wears no underwear to church, it is inevitable. No apparel can contain her body.

The foxtails:

Just as my friend and I were beginning to drift apart, I arrived late at a party where she had been for some time. Knowing the host well, I let myself in and went to hang my coat. There were a variety of other coats already, many I knew well, the gathering was small, the guests were intimates. And yet there on the pegs was a coat I didnt recognize. It was casually lavish, I remember it being furred, though maybe it wasnt. I remember it being dark. It had to be my friends coat, and yet it was a piece of her I didnt know.

Click here to download your very own printable Sula paper doll

Find our other paper dolls here

Julia Berick is a writer who lives in New York. She works atThe Paris Review.

Jenny Kroik is an illustrator and painter. She has created covers forThe New Yorker, and made illustrations forThe Washington Post,theLos Angeles Times, Penguin Random House, and more.