We can learn a lot by studying the systems that led to the emergence of the novel coronavirus, its fast spread around the world, and remaining effects. The world will be different afterward.

How did we get here? And where might we go?

Cocktail

Animal-to-animal mixing

If you’ve followed the COVID-19 story you’ve probably heard a lot about wet markets. Years ago it was normal practice for me to shop for food in them. I was actually taught to cook by people shopping in wet markets, where you can select a live chicken and return to pick it up, slaughtered. Or pick out a live fish and return to pick it up scaled and gutted.

But I’ve never shopped in a place like the Wuhan Huanan wet market, where COVID-19 may have originated. My market experience is brought to a new extreme in Wuhan (and many other locations). It’s instructive to think about why wet markets can be risky.

We have many examples of viral cross-species transmission that eventually infects humans. Ebola (believed to be transmitted from bats to humans) is an example, as was SARS (believed to be transmitted from palm civets to horseshoe bats to humans), and HIV (chimpanzees to humans). The Spanish flu (believed to be transmitted from chickens to pigs to humans) was another example. Note that the exact transmission paths of these diseases, as well as their places of origin are still debated. (And while the Spanish flu did not originate in Spain, its location of origin is also still debated.)

COVID-19 appears to have jumped from bats to pangolins and then to humans. But how did these species encounter each other closely enough to transmit viruses? The belief is that a particular wet market in Wuhan, China hosted enough different (and exotic) species in close confines for the jumps to happen.

Note also that this type of wet market carrying many exotic and wild species is not the norm but it has become more popular for reasons we’ll discuss later.

From the paper Bats and Coronaviruses, published January 2019 (11 months before the novel coronavirus outbreak was noticed):

Bats are speculated to be reservoirs of several emerging viruses including coronaviruses (CoVs) that cause serious disease in humans and agricultural animals. These include CoVs that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) and severe acute diarrhea syndrome (SADS).

Another paper to read on this (written in 2011) is Anticipating the Species Jump: Surveillance for Emerging Viral Threats. I’ll just quote these two sentences, written eight years before COVID-19:

Of the more than four thousand known mammalian species, ~50% are rodents and ~25% are bats. This rich species diversity, plus other ecological traits (high population densities and reproductive rates), suggests that surveillance efforts focused on rodents and bats could offer high value.

But why were bats in a wet market at all? I’ve written about the wildlife trade in China, related to scale effects from formerly poor populations quickly acquiring wealth and then spreading new consumer demand around the world.

Culture and history influence demand for physical items. An existing population that rather suddenly has money to spend means that a larger percentage of its people can act on their demands.

For example, rhinoceros horn, elephant ivory, cordyceps, and wild ginger mostly grow thousand of miles from their primary modern sources of demand. That there is demand at all for these items is rooted in historical medicinal preferences. But in the above examples, including that of the unlucky rhinoceros, either because of government restrictions or long growth cycles, there are limited ways to increase supply and harvest the product.

The inter-species cocktail is how we got to this epidemic. What about going forward? How does the way we live impact future outcomes?

I wasn’t aware that the change in Chinese wet market style came from a 1988 Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife that enabled small farmers to raise wild animals.

Some quotes from the English translation:

- “The state shall encourage the domestication and breeding of wildlife.”

- “Units and individuals that domesticate and breed wildlife under special state protection may, by presenting their domestication and breeding licenses, sell wildlife under special state protection…”

So the wildlife protection law actually resulted in the domestication of wildlife. Small wildlife farms grew to large commercial farms. Also illegal wildlife trade (as I wrote about in Anything at Scale). Then also the wildlife industry, which targets wealthier consumers, lobbying the Chinese government.

Epidemiologists have previously noted wet markets of the exotic style (wild animal mixing) as being virus breeding grounds. There were just many factors making it difficult for them to shut down.

People-to-people mixing

When it comes to countries outside of China that have been hit hardest, the question sometimes comes up: why Italy?

I originally thought that it was perhaps greater Italy – China travel flow, given that last year Italy joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). (Another early hard-hit country, Iran, is also in BRI.) But there might be something else going on that is more Italian in nature.

It’s speculation, but here is an analysis from Moritz Kuhn and Christian Baye that’s worth thinking about:

@christianbaye13 & me have been thinking about the big differences in mortality rates so far during the corona outbreak in Europe. The differences in case-fatality rates are humongous. Italy has one of 6% while countries like Norway, Denmark & Germany have rates still close to 0.

Young Italians live with their parents at much higher rates than other people of Europe. In many instances that makes for positive family bonds and health. But in the case of COVID-19 it may produce bad outcomes.

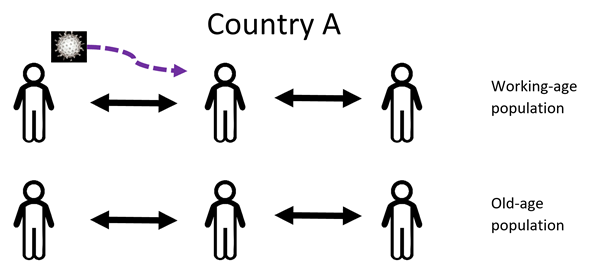

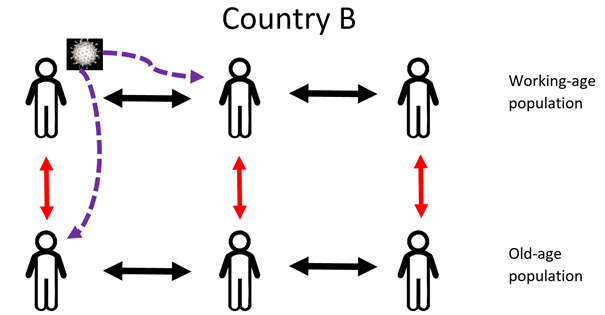

The idea is simple. Suppose, in country A almost all interaction is within one group of people, i.e. working age people hang out amongst themselves and as second group of people, the elderly, do the same.

At the same time in country B, interaction is often across generations. The young and the old live together and interact, for example, by taking care of grandchildren or young workers how still live with their parents as they cannot afford to live on their own.

There are certainly other variables at work, but this is a simple look at how an existing environment (family composition) may have unexpected outcomes.

If the Italian high mortality is mainly generated by a higher percentage of older people, then that effect would also eventually be seen in other countries with populations that skew older, rather than those that have a higher percentage of young and old under one roof.

In many other situations a mix of ages in a household can be a positive. However, the novel coronavirus, for reasons still not understood, impacts older adults more severely. This is unlike other pandemics, such as the 1918 flu which more severely impacted young people (due to infection that causes an excessive immune response in the body).

As I wrote in the distant past of 2018, in A City Too Familiar, naturally isolated places benefit from their isolation in times like these. But today there are fewer isolated places and more connectivity. Even what we may think of as isolated is not necessarily so. While 60 million people in the US live in rural counties, that does not mean that they are isolated. Research into the 1918 Spanish flu (not a direct comparison to the Wuhan novel coronavirus) shows both remote communities that escaped the flu and those that were nearly destroyed.

Best bets on true isolation are small islands or remote villages that see little in and outbound travel. But you’re probably not reading from a place like that.

Catalyst

Don’t seek to speed up the delivery of solutions as you also speed up the creation of problems.

One idea often heard is what if we could develop technology to deliver a new vaccine faster? The idea being that if new viruses continue to emerge, preventing them in healthy people could be a way to minimize effects without needing to change our behavior.

But there’s a problem with this idea. We still need to test new vaccines on people. It takes testing people in order to study side effects before we deploy the vaccine to the population at large. We can’t perfectly model outcomes. We also have not developed vaccines for the other, earlier human coronaviruses out there.

We could however, think about how to reduce environments like the Wuhan Huanan Seafood. That market sold badgers, bats, beavers, camels, civets, crocodiles, dogs, donkeys, foxes, giant salamanders, hedgehog, marmots, ostrich, otters, pangolins, peacocks, porcupines, rats, spotted deer, venomous snakes, and wolf puppies, among other animals. In close quarters.

Researchers had earlier identified this type of exotic wet market as a potential breeding ground for new viruses. But can these locations be eliminated? Perhaps, at least for a while, in the fallout from this climate.

What about delivering good information about activities to avoid or when to consider yourself high risk for COVID-19? In decades past, when information of that type was more centrally delivered (Emergency Broadcast System, a small number of news and radio stations) was it easier to present a central (and verified correct) message? I don’t believe that COVID-19 requires minute-by-minute updates. Those rapid updates, often delivered by user-generated content, can mislead.

Closeout

The COVID-19 pandemic will spark many changes. Some changes may improve the odds of minimizing the next pandemic. Other changes will just shift the problem around.

I believe that our heightened sensitivity to spreading contagion will reduce what we currently think of as freedom. Movement tracked and analyzed to assess potential exposure to the infected. Israel is already using mobile phone location tracking data (in the past used for counter-terrorism) in order to track proximity to coronavirus patients. Temperatures regularly taken in public and even at home.

What economic impact will we see from people quarantining themselves at scale? Is it possible for there to be a great, but hidden, loss of life from that too?

What about the long-term effects of keeping kids out of school? There are kids who get their only good meal in public school. How do they replace that meal? Does keeping kids home widen the educational divide? Some kids will have parents who can stay home from work, not worry about income, and provide a good home school education. Many others will watch TV all day. As for college classes that are now remote, will tuition finally decline? After all, many of the benefits of college (and what is actually paid for) are outside of the classroom and not related to formal education.

Even if the wet market environments that help introduce new viruses can be eliminated, there are natural environments where viruses jump species as well. Are we increasing the likelihood of species jumps in natural environments too? This is what happened with the Ebola virus.

The potential is there for other microbes too as we change systems. From the article Eradication’s Good Intentions:

“What could happen if the mosquito species that carry human malaria were eradicated?

People change their habits. Without mosquitoes keeping the human population away from prime mosquito habitats like swamps and rain forests, more people may move to these areas. People may then push out other animals and prepare unoccupied lands for logging and farming. Also, people may hunt and eat more “bush meat,” a source of other cross-species diseases, including Ebola and AIDS. Because the risk of malaria is gone, even though mosquito bites are still noisome, people may be less likely to empty collections of stale water, leading to other diseases supported by availability of this water. Impact elsewhere in the system: high?

I also believe that an unhelpful lesson to take from COVID-19 would be to assume that countries have only one style of management open to them. Since the world will face another pandemic situation again, should responses be both global and local in design? From the SCMP:

South Korea’s response has been a testing programme that has screened more people per capita for the virus than any other country by far. By carrying out up to 15,000 tests per day, health officials have been able to screen some 250,000 people – about one in every 200 South Koreans – since January. To encourage participation, testing is free for anyone referred by a doctor or displaying symptoms after recent contact with a confirmed case or travel to China. For anyone simply concerned about the risk of infection, the cost is a relatively affordable 160,000 won (US$135). Testing is available at hundreds of clinics, as well as some 50 drive-through testing stations that took their inspiration from past counterterrorism drills and can screen suspected patients in minutes.

Additionally, this comment related to the South Korean approach on the efficacy of lockdowns in some societies:

“Conventional and coercive measures such as lockdowns of affected areas have drawbacks, he said, undermining the spirit of democracy and alienating the public who should participate actively in preventive efforts.”

Consider

- Will the US and other countries finally consider it a national safety imperative to maintain pharmaceutical production capabilities for disasters?

- What rash change will this crisis spark which causes even more harm?

- The ad-supported business model of social media and some news organizations encourages sensationalism and became what people expect. However, when ad sales fall suddenly (as they must be doing now), social media and news organizations still produce articles that put their users on an emotional roller coaster. That seems like a lose-lose.

If you liked this post you might also like Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

—

A version of this post was previously published on the Unintended Consequences blog and is republished here with permission from the author

The post Coronavirus Cocktail, Catalyst, and Closeout appeared first on The Good Men Project.